By Airwaves Writer Tyler Colvin

In the boat building industry, the name Johnstone is about as close to a royal family as you can get. Ever since the first J/24 Ragtime was cast in the garage of 1975 by Rod, the family has dominated the boat building scene. Boat building has continued to stay in the family, with a board of directors made up of Johnstones, as well as a myriad of individual projects, including Peter Johnstone’s well-known Gunboat International.

The company that grew from the garage project, J/Boats, was in its infancy when Peter Johnstone was just 12 years old. When asked about how he got his start, his reply was, “Osmosis. Nightly dinner discussions with the family take over your thoughts at a young age.” He caught the bug early, learning to sail with his sister. “My older sister was very supportive of my sailing when I got started at age 7. She encouraged toughing it out on many difficult early days in a Sunfish as a tiny kid.” This was the beginning of what has been a storied sailing career, earning All-American sailing honors while at Connecticut College. He would go on to win multiple class championships and make several world record attempts.

Stemming from his love of the water and his family obsession with the boat building industry, Peter himself has played a big part in the advancement of modern boats. His first venture, Johnstone One Design, introduced the world to the retractable bowsprit on the One Design 14, revolutionizing sport boat design. Since then he has been involved with numerous other companies, including Sunfish Laser (pre-Vanguard Boats), Escape Sailboats and EdgeWater Powerboats.

“I love sailing. I love boats. And I love boat yards. Once you have done complex yacht projects, the rest of life seems pretty boring. It is not so much a job. It is a mission and an affliction,” he says, “It feels like I was placed here to push for new market segments and expand the capabilities and reach of sailing.” Indeed few have had even nearly the success he has had in the industry, and perhaps it is because his drive to be the best is unequaled.

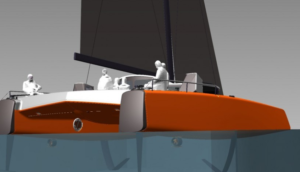

In 2001, frustrated by the lack of a performance cruising catamaran on the market, Johnstone set out to create his own. He wanted a combination of comfort, enjoyment and the ability to do hundreds of miles a day without sacrificing the other criteria. From this the 62’ Tribe was born. Again, Johnstone revolutionized the industry. Tribe performed beautifully and Gunboat International was born.

The industry standard for luxury catamarans, Gunboat has grown and changed over the years, but not without some pitfalls. “The industry is very cyclical. The fall of Lehman Brothers set us back 6-8 years. Recessions hit hard. You have to take the punches, pick yourself up, dust off, and set back at it.” He has stuck with it over the years and is reaping the rewards.

Despite getting a jump on the competition growing up in the First Family of boat building, Johnstone has earned multiple victories along his career path; revolutionizing the industry several times. He attributes his accomplishments to hard work and persistence, quoting, “Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “IF”, captures the life of a boat builder well. If that poem sounds attractive, then you are cut out for the challenges. If it doesn’t sound good, go elsewhere!” Positivity is a big contributing factor as well, and he offers sage advice for those starting out in the sailing industry: “Be willing to do anything at first. Be positive and gung-ho. Energy and motivation are always prized traits even if the work experience is not there yet.”

Gunboat International is based out of Wanchese, NC, and regularly posts openings in their workforce to the Sail1Design Career Center! If you are interested in getting your start in the industry, be sure to monitor the job postings for any new openings they, or other companies, may have.

Blog

Sailing Pinnies from World Cup Supply

World Cup Supply, a US Sailing MVP Member Benefit Partner, is proud to showcase its popular sublimated sailing pinnies. Worn by elite high school, collegiate and yacht club race and team programs and improved for 2014, World Cup Supply pinnies are an excellent way to increase visibility, show coordination while being safe and comfortable. You can visit our new Pinnie Design Guide, request a custom order quote and learn more at http://www.worldcupsupply.com/product/lycra-water-sports-bib-dye-sublimated/ or call 800-555-0593.

More about WCS:

Founded in 1991, World Cup Supply is a respected supplier of sporting event supplies. Located in Fairlee, Vermont the company has earned a reputation as an industry leader by providing the highest quality and innovative products.

Selden US Reports from the RYA Dinghy Show!

Selden Mast US is a Sail1Design team member and sponsor. Please check out these videos, and learn about exciting developments in UK youth and dinghy sailing, including new boats, classes, and sailing gear!

“Earlier this month we went over to the UK to check out the Suzuki RYA London Dinghy Show and made a few videos featuring some of the boats and products as well as interviewing some of the top youth sailors we found.” This is the largest dinghy show in the world.

INTRODUCTION VIDEO:

In the video below, we learn more about MULTI-HULL SAILING, especially the Spitfire Cat, the UK’s twin-trapeze youth trainer cat:

UK Youth Catamaran Class Information: http://www.youthcat.org.uk/

FULL PLANING MONOHULLS

YOUTH TO ADULT PROGRESSION: AERO & FEVA

FAVORITE NEW GEAR AT THE LONDON RYA DINGHY SHOW

Sailing Conditioning 101

By Airwaves Writer Tyler Colvin

Often times in sailing, races are won and lost in the weight room. Physical conditioning has come to the forefront in recent years as being just as important as developing boat handling skills. In fact, much boat handling can’t be properly practiced or executed without the proper conditioning base. This applies as much to keelboat sailing as it does dinghy racing, with emphasis on slightly different muscle groups.

As a US Sailing Level 3 Race Coach, Collegiate Coach and NSCA Certified Personal Trainer, I am in a unique position to provide sailing specific workouts. This weekly series will be mainly aimed at High School and College aged dinghy sailors and can be conducted without any equipment. Any questions can be directed to me at [email protected]. Upon request I can also provide personalized workouts depending on your or your teams needs.

Disclaimer: As with any workout program, please consult your physician if there are any questions regarding your ability to exercise.

Week 1: Building Blocks

This circuit based workout concentrates on functional strength and muscular endurance. Core strength is paramount in dinghy sailing, especially on windy days. In this Week 1 circuit we will work on full body strength using bodyweight exercises, requiring nothing but a stopwatch, water and an open place.

Warm Up:

-10-15 minutes. Go for a run, ride the bike, stair climber, something to get the hear rate elevated and a quick sweat going.

Exercises x20, 3 times through

–Lunge: alternating left/right, each step should be long enough so that your front knee is at a 90-degree angle and back knee is touching the ground. Think about dropping your hips down instead of getting your weight over the front of your toe (on your front foot).

–Push up: From your knees or on your feet, keeping your back straight, lead with your chest into the ground until your elbows are at right angles.

–Mountain Climbers: From push-up position, alternate bringing your knees towards your chest.

–Body weight squat: Standing with legs slightly more than shoulder width apart, drop your hips back like you are sitting down in a chair.

Work Out: Do each exercise for 1 minute with a 10 second pause in between. 2 minute rest in between each set, cycling through 3 times.

–Plyo Squats: Similar to the bodyweight squat, at the top jump as high as you can, landing into a squat.

-Full Sit Ups: laying flat on your back, hands over your head, sit up and touch your ankles.

-Push Ups: From your knees or on your feet, keeping your back straight, lead with your chest into the ground until your elbows are at right angles.

-Line Hops: If you have a line, great, if not, imagine one. Jump back and forth across this line, speed does not matter just continual motion for the full minute.

-Jump Rope OR Burpees: Burpees: starting in pushup position, go down, come up, bring both feet in towards the chest in one motion, jump up in the air and reach towards the ceiling.

Core: Each exercise x20 (except plank), 3 times through

–Plank (30 seconds): In pushup position, settle onto your elbows. Back should be straight with no arch in the lower back. Glutes are tight as are the abs.

-Alternating Leg Lift V-Up: Laying flat on your back arms and legs out straight, reach your right arm and left leg up and touch them above your belt. Try to get your shoulder blade and opposite hip off the ground. Alternate.

-Alternating Superman: Laying on your stomach with your arms and legs out stretched, raise your opposite arm and leg while keeping them straight.

-Russian Twist: Sitting on your tailbone, raise your legs off the ground several inches. Twist your upper body back and forth touching the ground on either side.

Club Profile: Cape Cod Sea Camps

News Flash: Cape Cod Sea Camps is Hiring! View their open jobs HERE

The Cape Cod Sea Camps Mission

Through personal commitment and dedicated to the development and guidance of youth we will provide a unique educational environment in which individuals have fun and realize their worth and potential.

Working Philosophy

The Cape Cod Sea Camps are preeminently dedicated to the guidance of youth and founded on the principles of love for fellow men and appreciation of God’s world and people. Camping is a joyful educational experience carefully designed to allow children to develop all aspects of their personalities – physical, mental, spiritual, and emotional. Children at camp are viewed not merely as “miniature adults”, but as youngsters who need constant care and attention to help them develop into happy, productive, sensitive men and women. Camp provides a microcosm in which a child’s attitudes will be greatly influenced and in which he may “experiment” with new types of behaviors in a controlled, responsive environment. Camp helps children learn about themselves as they learn about people and natural beauty around them. As each child is respected as an individual, so he is encouraged to become sensitive to the unique aspects of humanity in others. Children are helped to overcome the insensitivity inherent in categorizing individuals by group associated through living, working, playing with others of both sexes, and various ethnic, religious and racial backgrounds.

The Cape Cod Sea Camps are “people places” where the needs of children and abilities of the staff determine the program; no tradition is so entrenched that is wisdom cannot be scrutinized and no proposed innovation is too radical not to merit serious consideration. The essence of the camp is the multifaceted composite personality of every person who has influenced it throughout more than three quarters of a century, and the substance of its future has yet to be determined by those who will give of themselves tomorrow. Everything that happens at Cape Cod Sea Camps, however, is strongly imbued with the moral consciousness that it takes time for a child to grow and a deep conviction that camping is indeed an educational experience, and unlike any other anywhere.

- Camping is an Educational Experience

- Camp develops all aspects of a camper’s personality-physical, mental, spiritual, emotional

- Each child is respected as an individual and encouraged to become sensitive to the diversity in the world around us

- Camp is a “people place”

History of Cape Cod Sea Camps

The history of the Cape Cod Sea Camps, Camp Monomoy for Boys and Camp Wono for Girls, is the story not only of two children’s camps, but also of a family, the Delahantys. More than any other single individual, Robert J Delahanty created and crafted the essence and character of the Sea Camps. It was his vision that came to life in 1922 and which still endures today. With the inestimable assistance of his wife and partner, Emma Berry Delahanty, and later, their daughter, Berry Delahanty Richardson, Captain Del gave substance to his dreams, founding a business and embarking on a calling.

Captain and Mrs. Del dedicated themselves to serving youth. From the beginning of his career, Captain Del passionately believed in the educational and spiritual value of properly constructed recreational activities. His brilliance shone through in his camp program offerings, and also in his innate sense of what was good and useful for children. He understood that every child needs to be best at something, whether hitting a baseball the furthest, sailing a course the quickest, swimming a distance the fastest, or simply having the most perfect bed in camp.

Today the Delahanty tradition not only endures, it flourishes! Captain and Mrs. Del’s granddaughter, Nancy Garran, now steers the ship with the same commitment to excellence laid down by her grandparents and her Aunt Berry.

News Flash: Cape Cod Sea Camps is Hiring! View their open jobs HERE

Work at CCSC

Our counseling staff is comprised of college students, graduate students and teachers. We are looking for individuals who have the desire and talent to make a difference in a child’s life. It is probably one of the most demanding, yet satisfying jobs on the planet. Our staff are chosen carefully, with an eye on their ability to be good role models, contribute positively to children and to teach specific activities. There are 90 Resident Camp counselors, 74 Day Camp counselors and 28 supervisory staff.

Camp Season

The camp season is 7 weeks long for the campers, June 29th – August 16th, 2014; and the day camp season is July 1st – August 16th, 2014. The commitment for staff is approximately 8 weeks, June 23rd – August 18th, 2014. Counselors must attend the staff orientation prior to the campers’ arrival and remain at camp after the campers’ departure until their responsibilities are completed.

Campers

There are approximately 380 campers ages 8-17 in our Resident Camp and 300 campers ages 4-17 in our Day Camp.

In each unit there are 5-10 counselors and a Head Counselor, augmented by 4th year Junior Counselors. At the Resident Camp, there are always at least two counselors in each cabin such that the counselors have every other night off and one day off per week as assigned by our Program Director. Counselor areas are simple but are separated from the camper areas. Most all cabins have bathrooms attached and all cabins have electricity. Shower houses are adjacent to the cabin areas.

Activities

Our Program Director assigns counselors to activity areas on a weekly basis. Activity periods last approximately 1 hour. Depending on the number of campers taking an activity, there are a proportionate amount of staff assigned for coverage, i.e. 25 campers in archery would have 4 staff assigned. Sailing, water-skiing, windsurfing and canoeing are offered as all-morning or all-afternoon activities. The major activities we hire staff to teach include: Sailing, swimming, tennis, arts and crafts, drama, woodworking, archery, riflery (BB’s and .22’s), photography, nature, landsports, dance, newspaper/good books/creative writing, cycling, snorkeling, waterskiing, kayaking, windsurfing. We encourage counselors to introduce new activities within the confines of our camp philosophy.

Sailing Staff

Members of the sailing staff must have current certification in CPR, First Aid and Lifeguarding or Small Craft Safety (sailing, canoe/kayak). Other certificates are welcome such as US Sailing Level 1 Certification, USCG Launch Tender License (or higher license).

ICSA TEAM RACE RANKINGS, 3/10/2015

About Sail1Design

Sail1Design is a grassroots organization, by sailors for sailors, dedicated to the one-design, youth, high school, college, and one-design sailing communities. Born in 2007, Sail1Design has grown considerably, and reaches out to all sailors wishing to enjoy and learn more about our sport. We have three main areas of business:

SAILING/MARINE INDUSTRY CAREER CENTER & JOB BOARD

We offer sailing’s #1 Career Center and Job Board, always chock full of incredible sailing job opportunities. Our comprehensive career center also offers job seekers the ability to create their own web page, highlighting their experience and posting their resume. Likewise, employers can search our resume database to find the right match for that open position. Sail1Design is proud also to be the official job board of the Intercollegiate Sailing Association (ICSA), and the US High School Sailing Association (ISSA).

MARKETPLACE & PROFESSIONAL BROKERAGE

Unique to the industry, Sail1Design hosts and manages an active private, by-owner marketplace, focusing on performance and one-design sailboats & gear. For all boats under 25′, our ads are free. What makes us different is that we also provide, side-by-side, professional brokerage services as well. We have had great success helping our sailing clients market and sell their boats, using our powerful client base, social media, and the brokerage industries multiple listing service to ensure your boat gets noticed.

AIRWAVES NEWS & CALENDAR

S1D also hosts Airwaves, an interactive, user fed Sailing Calendar and informative Sailing News, Articles, tips, & more. Airwaves has developed a great niche in the sailing publication world, and now boasts a seven-member staff of dedicated sailors, all contributing to our varied content.